February 7, 2019

New focus on forgotten American artists Julia Thecla and Sonia Sekula

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. – Julia Thecla and Sonja Sekula are two American artists of the early to mid-20th century who deserve the attention they’re attracting as a result of artworks entered in Myers Fine Art’s February 17 auction. Thecla’s ethereal “The Last Lover” and Sekula’s abstract “Les Dernier Chateau,” or “The Last Castle,” are examples of the extraordinary talent these women possessed.

Thecla’s painting of a young woman hails from the estate of gallery owner and artist David Porter, who was a lifelong friend of Thecla’s. Sekula’s abstract trapezium work originates from a Southold, Long Island, N.Y., estate. Southold, N.Y., is also the home of renowned artist and gallerist Betty Parsons, who exhibited Sekula’s work in the 1940s. [Parson’s sculpture “Sea Horse is also among the artworks being offered in the auction].

Perhaps not regarded as contemporaries in the traditional sense, these two fascinating artists have several things in common. Both exhibited with notable collectors in the year 1948 – Sekula with Betty Parsons and Thecla with Peggy Guggenheim. Both were explorative in their artistic techniques. And sadly, both met tragic ends. Thecla passed away at a charity home outside of Chicago, destitute and forgotten. Sekula took her own life after decades of battling mental illness. Neither of these great women was deserving of their ends, and one glance at their work would confirm that assessment.

Julia Thecla’s early life remains a mystery. Born Julia Thecla Connell in a small Illinois town in 1896, she began using her middle name as a surname for unknown reasons when she estranged herself from her family and moved to Chicago in the 1920s. She studied for two years at the Art Institute of Chicago, occasionally working intermittently as an art restorer to support herself. Her work can best be described as magical realism, or even surrealism, a style that spilled over into her daily life. Thecla was known for her childlike persona and costumes, which became an early type of performance art.

David Porter recalls, “She wore tiny vests, quilted skirts with tight waistbands and flaring hems, and high-button shoes. She carried the most peculiar kind of little purses, complete with tiny lipsticks and make-up. Her odd flat-brim straw hat frequently had a hatpin flaring out at a raking angle.” This surrealist-inspired femme-enfant can be seen as the precursor to modern day Harajuku and Lolita fashions, with emphasis on Victoriana and miniature details.

Thecla also caused a bit of a sensation when, dressed in her eccentric style, she would walk her pet chicken on a leash through the Chicago suburbs. She kept many pets in her studio, among them chickens, rabbits, cats, and a pigeon she dyed pink. While some have dismissed these acts as indicators of insanity, Thecla created spectacles of these types as means of concealing her true shyness.

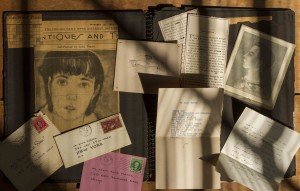

While intentionally immature in her dress and persona, Thecla was nonetheless a woman capable of great passions. She considered David Porter to be the love of her life, and her letters to him are evocative of the ethereal ambience captured in her art. Thecla used diminutive envelopes and cards, on which she wrote in flowing calligraphy. In one letter, she describes a dream to Porter:

“It was a wonderful journey through the still air—through cold trackless blue, past flaming suns and tender stars, among countless meteors that changed dark to day, among the illimitable midnights of the universe, and away from the far-off Earth, where men and women love and suffer, and the best can only pray. But I saw no star-fields like those eyes of yours, my Heart, and I followed untiringly the grey, shadowy mist that enveloped you, until we reached an endless plain of night.”

Thecla acknowledged that Porter did not return her affections, and wrote, “Fate may deny me love, but not loving. The honor of it is not yours, but mine—I am proud that I am enough to love you.” Instead of the then-requisite path of marriage and family dictated by society, Thecla used her energies to work prolifically. She was a set designer for theaters and ballets. She also produced and exhibited her own work. Her career culminated in her participation in Peggy Guggenheim’s “Women” show in 1948.

Having lost touch with Porter and many of her colleagues, Thecla’s vision began to deteriorate during the 1960s and she ended up in a Catholic charity institution for homeless women in Chicago. Porter discovered her there and was shocked at her diminished state. He sent her art supplies, but never made contact again until her death in 1973.

The painting being offered in Myers Fine Art’s February 17 auction of 20th Century Decorative Arts that includes paintings, prints, sculpture, mid-century modern furniture, glass, pottery, silver and jewelry, is one of Thecla’s quintessential works of art, and it retains the original Museum of Modern Art loan label on verso. It hauntingly depicts a young woman being handed a bouquet of flowers from a mysterious hand. The detailing and rich colors are exquisite, and the overall effect is true to Thecla’s magical realist style. The spectral painting is estimated at $15,000-$25,000.

In contrast to Thecla’s upbringing, Sonia (also spelled Sonja) Sekula began life in a distinctly more charmed manner. Born in Switzerland in 1918, Sekula and her family moved to New York in 1936, where she was surrounded by exiled European artists and writers. She attended Sarah Lawrence College and eventually became well known within the Surrealist and Abstract Expressionist movements of the 1940s. She was acquainted with such notable figures as Jackson Pollock, Andre Beton, Max Ernst and Robert Motherwell. In 1948 Sekula exhibited with Betty Parsons and, later that year, with Peggy Guggenheim.

Although she became an enigmatic figure and was praised for her talent, Sekula was nonetheless plagued by chronic self-doubt of her artistic capabilities. Unfortunately, these mental barriers prevented her from producing work for long periods of time when she sought treatment. Her family was forced to relocate back to Europe, where, isolated from the art world, Sekula succumbed to her inner demons and committed suicide in her Zurich studio in 1963, at the age of 45.

Grace Glueck of The New York Times reviewed an exhibition of Sekula’s work at the Swiss Institute New York in 1996. Glueck wrote: “Sekula relied heavily on automatic writing, a kind of doodling in which the pen or brush, guided by the subconscious, is allowed to roam freely over the surface, making marks theoretically liberated from prevailing modes.” The effect is “distinguished by overall calligraphic markings and incidents on painted grounds.”

Sekula’s painting entered in the Myers Fine Art auction is a fine example of the style described by Glueck. Titled “Les Dernier Chateau,” or “The Last Castle,” the oil painting is trapezoidal in shape, signed and dated “1947” at lower right. It is estimated at $4,000-$6,000.

Although both of these artists have been tragically forgotten and misunderstood, if remembered at all, their obvious talent is seen in the work they produced throughout their lifetimes. Both Thecla and Sekula embodied their respective particular styles of painting. They excelled at visually stimulating all who observed their work, and it is Myers Fine Art’s hope that these works will be appreciated by all who view them.

View the fully illustrated catalog for Myers Fine Art’s February 17 auction and sign up to bid absentee or live via the Internet at:

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/catalog/135594_20th-century-decorative-arts-feb-17-2019/

Collection of ephemera related to Julia Thecla (American, 1896-1973) and the object of her affections, gallery owner and artist Edwin Porter. Myers Fine Art image

Sonia Sekula’s (Swiss-born American, 1918-1963) painting “Les Dernier Chateau,” or “The Last Castle” on display at Myers Fine Art’s pre-auction preview. Estimate: $4,000-$6,000. Myers Fine Art image